Pauline’s Memories

My mother, Pauline, worked in the family glass business, mostly before I was born. Those were the early days of the Hamon Glass Company, long before Bob took over the company and turned it into a modern glass studio. Mom was happy to help the family out, but she could not have known that she was part of a dying operation, for the explosion of plastics manufacture would soon spell the end of the handmade communion glass industry.

She remembers working with the annealing machines used for communion glasses, which Hamon Glass made in great quantity, before plastic glasses replaced the more fragile glass versions. The annealing had to be exact and thorough to make sure the glasses were safe for use. I’d like to add that I prefer the glass version, for plastic just doesn’t do wine (or grape juice) justice. Also, mom helped to roll the diminutive glasses in tissue paper and pack them for shipping. It was a job that required quick fingers and manual dexterity.

She said the company made three different sizes — 33, 44 and 55 — but most churches ordered the small size (perhaps some were worried that their flocks may get too much wine from the larger sizes). Hamon Glass shipped communion glasses all over the country, to churches and temples far and wide. My grandfather, Okey Hamon, was proud of his communion glass business, since he was a devout man and an active preacher, who had his own country church and preached as an evangelist at other churches. Mom recalls that one of the biggest customers was a Baptist church in Philadelphia.

My mother worked alongside Aunt Ernestine, Bob’s wife, who was a tireless worker throughout the factory. She trained most new employees, except for the glassblowers, and did whatever job that needed doing.

As a small boy, I recall walking into the packing room and seeing tall pyramids of wrapped communion glasses sitting on a wooden table under a hanging light, basking in a yellow glow. How magical. To me, the packing room was a cozy cave, like so many of the rooms in the factory, and I could think of nothing better to do than to explore each and every one.

Pauline said it was fun working in the factory, but the work was never easy. And she was always afraid of making a mistake. In time, she learned to pack the glassware very precisely to prevent breakage during shipping.

During the winter months, it was cold in the packing room, and periodically Pauline had to warm her hands up frequently by the glory hole in the adjoining glass shop. I remember doing the same thing when I was hanging around the factory.

The Communion Glass Process

I loved watching the glass men make communion glasses. It would take two men. The gatherer would take the blow pipe and gather glass on the end, about the size of a large marble, roll it out on the marbler, a large slab of metal, and blow a puff of air in it and hand it to the blower. The blower would drop the glass into the mold, spin the pipe, shape it and let it cool, before knocking it off in the annealing chamber.

Then a machine trimmed the top and the glass was passed through a series of five flames to smooth the rough edge, before the glass was annealed. My mother did some of the annealing. My father recalls how she grimaced in pain one day, while annealing communion glasses, when she was pregnant with me. Dad made her stop, and that was all she worked that day. Maybe I was kicking too hard.

Going for The Record

Uncle Bob and my father were highly skilled glassblowers. One day they decided to try for the record by producing the most communion glasses in a day. They worked non-stop for eight hours, and made 2,800 glasses, which became the new record for the factory. Many tried, but no one ever broke the record, I am told.

Robert Hamon’s Creative Approach

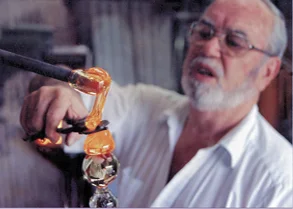

It’s been sixty years or so since my family’s glass company made communion glasses, but Bob sometimes crafted special order glassware for religious services. And, due to his love of all things spiritual, he found joy in doing so. My uncle was a deeply inquisitive thinker, who used his wonderful, analytic mind to question everything. In his lifelong search for meaning, he explored psychology, philosophy and religion, and his open mind was never so full of knowledge that it could be considered closed. That was the beauty of my uncle — he had a delightful open mind, and he could never learn or know enough.

This same attitude could be seen in his glass work, too, since he was always trying new procedures and ideas, and was sensitive to dream motives, and expert at including them in the construction of his signature free-form art pieces.

A Legacy In Glass

Every day, I am thankful for my glass family and the legacy it has left us. This morning, when sitting down with my mother, and reminiscing about the good, old glass days, I felt a sense of pride and joy swelling in my chest. What a pleasure it was to grow up in this family, and to form a relationship with decorative glass, and to have glass in my soul. As my mother recounted her glass days, I felt a fond and lovely energy emanating from her, a warmth that is nearly impossible to describe.

Recently while on my travels, I visited a small gallery in West Virginia and discovered a piece of Hamon glass. The sense of pride I felt is difficult to describe. The owners said the vase was not for sale because they had become too fond of it to ever part with it.

I’m sitting in a cold corner of a little cafe’ as I write this blog post, delightful scents drifting in the air from the kitchen, along with snippets of conversation from the guests. I find myself stopping to blow on my nippy fingers, recalling the days of my youth when so many times I stood in front of a hot glass furnace, warming my cold hands in front of one of the most beautiful sights I’ve ever observed, a furnace full of molten glass, orange and red, and as fiery as the planet of Mars.